Paul Linhares was introduced to paddling work when watching Yixing teapot makers use paddles to skillfully shape clay slabs into beautiful pots. Years later when he wanted to make a bottle shaped like a fish, he remembered the Yixing potters and decided to use a paddle on his wheel-thrown work.

In today’s post, an excerpt from the Pottery Making Illustrated archive, Paul shares his techniques for throwing a bellied-out vase and paddling it into shapes that are perfect for surface decoration. – Jennifer Poellot Harnetty, editor

Wheel Work

The potter’s wheel is the primary tool in my work. During the mid 90s I worked as a production potter making several hundred pots a day. The skills developed by this repetition and focus on technique paid great dividends.

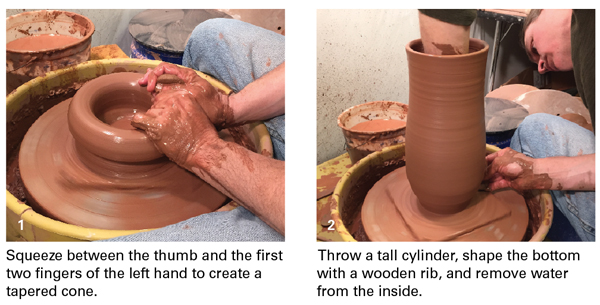

Clay absorbs less water when less time is spent centering and pulling up the cylinder, which makes the pot stronger during shaping. After centering the clay, open it with your left hand and lean your upper body back while pulling the floor of the pot toward your right hand. The left hand will then be wrapped around a low doughnut of clay. This can be pulled up using a claw pull. Begin squeezing between the base of the thumb on the outside of the pot and the first two fingers on the inside (figure 1).

While beginning to squeeze with the left hand, wrap a damp sponge over the top

of the doughnut with the right hand, compressing the rim and leaning slightly inward to remove any off-centered feeling in the clay. Wait for the clay to center then begin squeezing and leaning in harder, all while continuing to set the rim with the sponge. Pull the doughnut into a tapered cone shape that can then be pulled taller with any method.

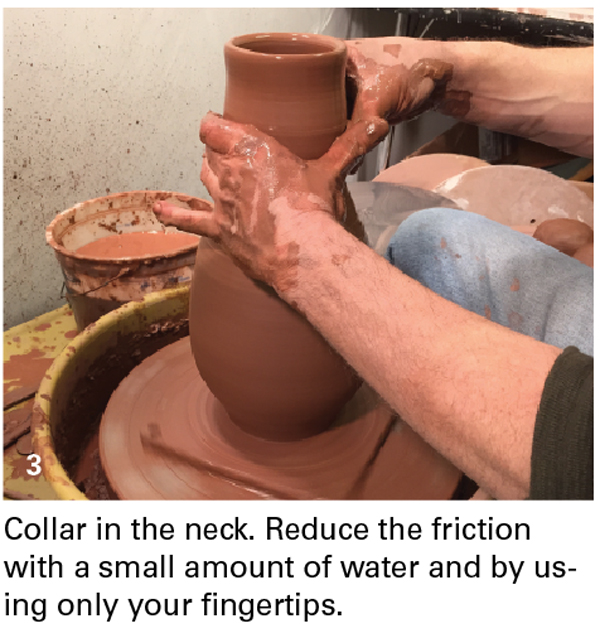

To make a bellied-out vase with a narrow foot and neck, pull the walls upward, keeping the clay that supports the belly and the spot where the neck meets the shoulder slightly thicker by releasing a little pressure during the pull. The water is removed from the interior floor and a wooden rib shapes the underside of the belly before the neck can be closed (figure 2).

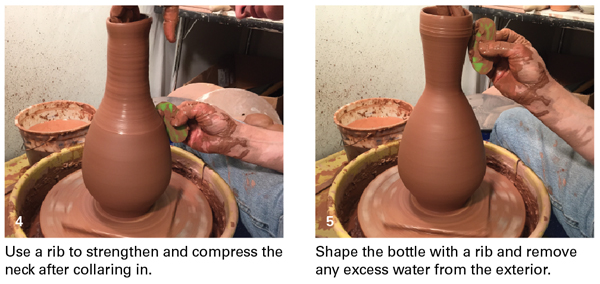

Collaring in the neck of a pot can be tricky business. The more friction applied to the top of

the pot, the more likely it is to buckle and twist at the bottom. Use a sponge to get water on the neck while being careful to keep it from running down and weakening the bottom of the pot. Reduce contact friction with the pot by using thumbs and fingertips to make several passes bringing in the neck (figure 3). As it constricts, the clay in the neck begins to thicken and wrinkle, so every few passes do a pull with fingers or a throwing stick to strengthen the wall then re-compress the clay with a rib (figure 4). All of this activity exaggerates any off-centeredness in the pot. If it’s slight, leave it alone and hide it under a newly compressed rim, otherwise, slowly introduce a needle tool to the side of the neck and cut off the

wobble. Finish shaping the pot with a flexible, rounded, rubber rib (figure 5).

Paddling the Form

I was first introduced to paddling by watching Yixing teapot makers. The skill they exhibited in shaping their thin, slab-built forms with paddles was inspirational, but it wasn’t until years later when I wanted to alter thrown bottles to make fish shapes that I began to use the technique in my own work.

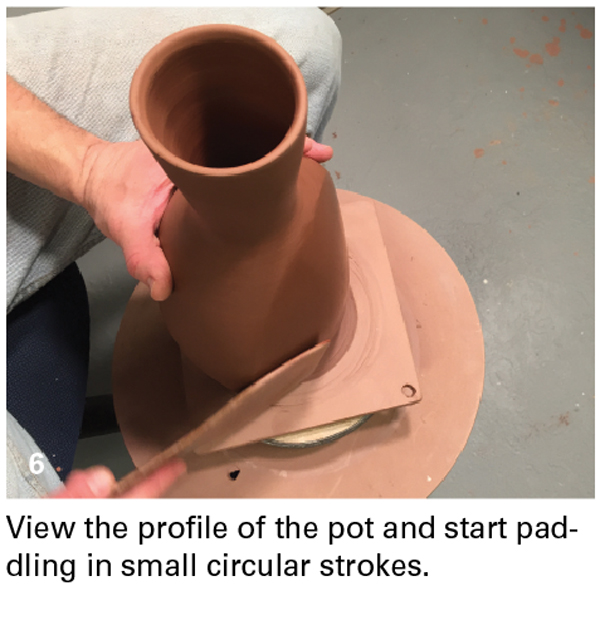

Once the bottle form has set up to leather hard it’s ready to be shaped. The pot will stick to the paddle if it’s too wet and crack if it’s too dry. Wooden paddles should be sanded smooth, making sure to round any edges or corners that might dig into the pot.

Begin in a position where you can see the profile you’re trying to alter and experiment with holding the piece in the hand or setting it on a banding wheel. Hit the pot with the paddle, moving in a circular motion instead of straight into the pot. The smack, stick, and stretch of this action happens in a fraction of a second, so imagine the paddle is a brush used to push the clay toward the desired shape (figure 6).

Begin in a position where you can see the profile you’re trying to alter and experiment with holding the piece in the hand or setting it on a banding wheel. Hit the pot with the paddle, moving in a circular motion instead of straight into the pot. The smack, stick, and stretch of this action happens in a fraction of a second, so imagine the paddle is a brush used to push the clay toward the desired shape (figure 6).

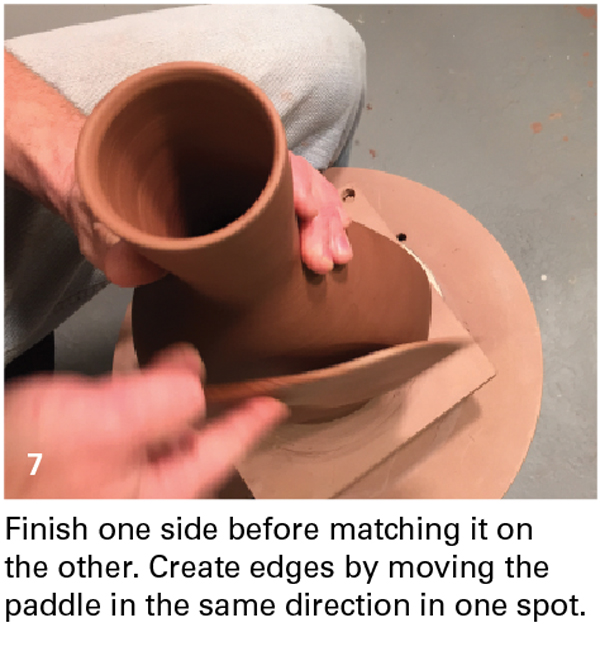

Sometimes, the pot gets soft again as it’s worked, requiring it to firm up again before continuing. It’s best to finish shaping on the first side before trying to match the form on the other side (figure 7). Working in one place on the pot and rotating the paddle in the same direction will cause an edge to form, so move the paddle around the work area until it’s time to set an edge.

There’s a dynamic relationship between the starting form and the finished piece, which doesn’t always go as planned. If the pot is too fat, interesting and even awkward folds can form on the bottom or sides, but instead of throwing pieces that look like mistakes away, it’s better to finish the process and see what happens. I always tell my students to fix their problems on the next piece—in ceramics we learn in a series.