With today’s high-tech computerized kilns, you may have wondered why pyrometric cones are necessary when firing your ceramic art. Even with all of the advances we have seen in the digital age, the best way to gauge what is happening with your work inside the kiln, is STILL looking at these magic cone-shaped doodads.

It all has to do with heatwork and in this post, Tina Gehart explains these fascinating little tools. She also explains what all of this has to do with synchronized swimmers! – Jennifer Poellot Harnetty, editor

A pyrometer measures temperature, but pyrometric cones measure heatwork. If you’ve been wondering what the pyrometric cone definition is, how pyrometric cones work, and what any of this has to do with synchronized swimmers, read on!

Cones: A Continuum from Clay to Glaze

There is an old saying that you plant peas when lilac leaves are the size of mouse ears. Planting according to an indicator plant takes advantage of the complex growth triggers in plants and follows them instead of measuring individual factors (day and night temperatures, rainfall, day length, soil temperatures). We allow the lilac bush to be our effective guide. We wait for the visual indicator of lilac leafing, and then we plant the peas.

Pyrometric cones are the equivalent of indicator plants when it comes to firing work. They are made of the same ceramic materials as our wares, so cones respond to firing the same way our clays and glazes do. Cones are designed to respond at consistent intervals that, when the cones are used correctly, will remain consistent throughout the kiln and from one firing to the next.

Pyrometric cones have been engineered to respond to two things, the first is low melt viscosity. As the heatwork in the kiln increases, the cone begins to melt. It develops a glass phase, and as it does, that glass phase becomes less viscous. It begins to flow.

Cones are engineered to respond to gravity as well. The cone form is designed with a spine that is the longest and strongest edge. It positions the cone in an 8° tilt away from vertical when the cone is stood on its base. In this tilted position, gravity takes hold of the cone and pulls. As heatwork increases and the glass-phase viscosity drops, gravity’s effect on the cone becomes apparent, and it bends toward its bending face—much like a bowl on the wheel when the clay is too soft, and the flare becomes too wide. The cone is having a precision flop.

In the example, the bowl is soft not because of melt viscosity, but water content. During firing, a bowl can present mechanics that are truly parallel to the cone, due to glass-phase development and gravity. This is pyroplastic deformation in its classic sense, the bending of clay due to low-viscosity glass phase.

Cones exist theoretically on a continuum between glaze and clay. Fire clay hot enough, and it will be a glaze. Fire that same clay a little less hot, and it will bend if in the proper position. Systematize the compositions with great enough precision, and those clay cones will bend in a continuum like a team of synchronized swimmers cascading into a pool.

The Cone System

The cone numbering system has a virtual zero in the center. Much like negatives numbers in math, cones farthest left of zero are lower heatwork than those closer to zero. These numbers on the left have an 0 (“oh”) in front of them. This 0 is not just a place holder. It is spoken, not as zero, but as “oh.” Cone 04 is very different than cone 4. Always say the “oh.” It indicates left-of-zero.

Cones are made for a range of heatwork measurements. The standard spectrum for studio ceramics spans cone 022 to cone 12, covering four firing ranges: ultra-low-, low-, mid-, and high-fire. Ultra low includes firing for lusters, overglazes, enamels, decals, and glass work (1). The bold-faced cones (018, 04, 6, and 10) are team captains of their zones, the archetypal cone used in that firing range.

Using Cones Well

Pyrometric cones have several practical uses in the ceramics studio. As firing measurement, witness cones (viewed through a kiln spy/peep hole) are the most accurate measure of a kiln’s firing progress, and for deciding when to shut down the kiln. Since cones act like clay and glaze, some ceramic artists fire “cones only” (often for wood, salt, and raku)—no pyrometers, kiln sitters, etc.

Cones are good safety nets in both computer- and sitter-fired kilns. In addition, they are important for calibrating your kiln sitters and customized firing schedules. Using cone packs throughout a kiln can give information about the evenness of the heatwork throughout the kiln, and stacking adjustments can be made to minimize cone differences. Even atmosphere and ventilation information can come from your cones (bloating, color change, hardshelling).

Always wear appropriately rated welding goggles when viewing cones in a kiln firing. Prolonged exposure to infrared light and intense heat can be damaging to both the retina and cornea.

Advantages of Good Cone Pack Form

A good cone pack gives you relative information about your current firing. A great cone pack gives you consistent, calibrated, reliable, and comparable information across all of your firings. To get the most out of your witness cone packs, you should always:

1) Build your cone pack with at least a warning cone, a target cone, and a guard cone. Know where you are aiming to fire. Know when that point is approaching, and know how much higher the firing has gone if the target cone has fallen faster than expected.

2) Build cone packs with all the cones’ spines aligned with either their left or right faces. This allows them to fall slightly forward instead of directly to the side and to fall fully and uninterruptedly to the down position, instead of landing on each other. Too often I see quickly made cone packs where all of the bending faces point right into the prior cone. The firer inevitably questions the cone pack: Is that cone 10 halfway, or is cone 9 just holding it up?

3) Set each cone with two inches exposed so that gravity works on it properly. Less exposed, and the cone will fall later than its standard. Too much exposed cone may allow the cone to fall too soon, and/or run the risk of the cone simply falling out of the pack.

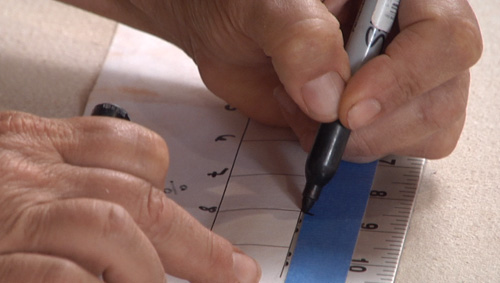

4) Angle the cone to 8° from vertical. The base is designed to put the cone in this position. Simply hold a cone upright, flush with the tabletop, and set your cones in the cone pack to match the angle. If your cones are set at greater than 8°, they will fall sooner and slightly faster. If set less than 8°, the cones may backbend, or fall in the wrong direction entirely.

5) Record the behavior of the cone pack throughout the firing, particularly in combustion kilns (gas, wood, oil). Doing this for all firings allows you to compare results of your firing adjustments, fuel/combustion settings, and stacking arrangements. Recording in consistent log language for your cone readings can help when sharing firing information.